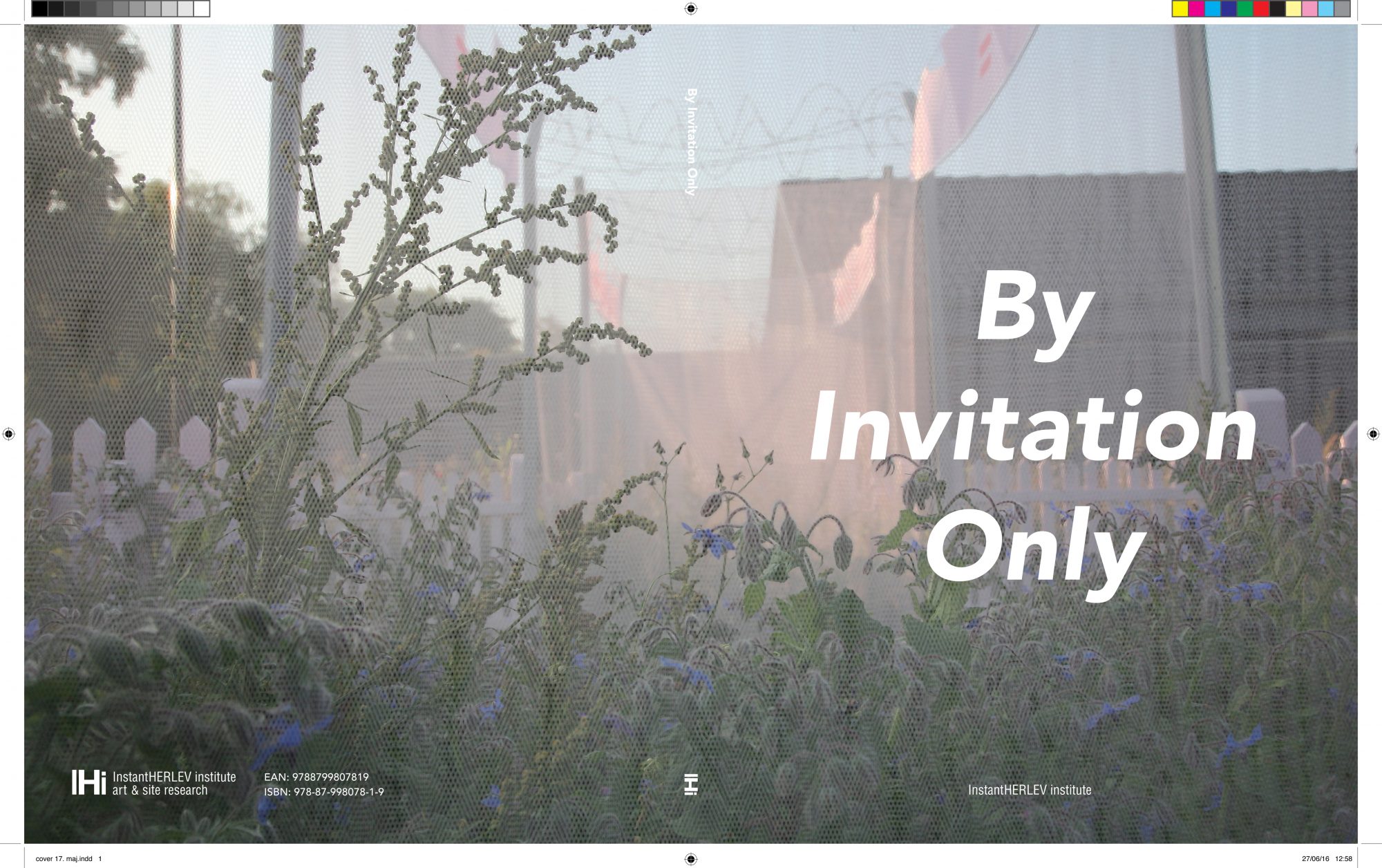

Cover of exhibition catalog ‘By Invitation Only‘ curated by Lucia Sanroman. Catalog designed by THE WINTER OFFICE. Published by InstantHERLEV Institute, 2016.

Postscript for the Post-Contemporary Artist-run Space

By Hugo Hopping

June 2016

From the 'By Invitation Only' 10 year anniversary catalog

Published by InstantHERLEV Institute, 2016

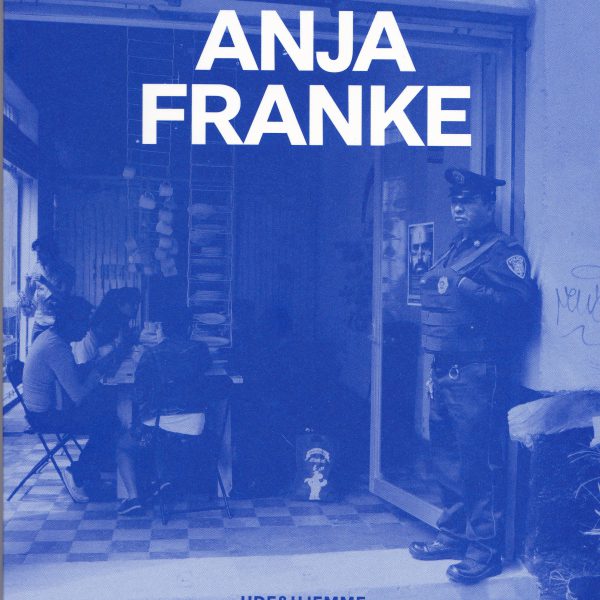

Two pictures, the same view of a front yard and sidewalk, one taken in May 2004 and another in May 2014, moving forward over the years between new technology, social opinion, political changes, aging neighbors, and an understanding of the future that holds over us climate change and its mitigation. One wouldn’t imagine that a suburban home – settled on the rim of one of the most unsuspecting and unwary areas of Copenhagen’s capital region – could be a venue for activity and exchange between a set of creative and artistic people from all over the world. These same people are responsible for changing the character and surface documented in these two images. Most of whom, upon invitation as producers, viewers, users, loafers, lovers, or creative precariats, have developed ten years of exhibitions right out of the house, yard, or surrounding community of the Danish visual artist Anja Franke.

Located in the municipality of Herlev (pronounced: hair-lew) InstantHerlev Institute stands alone, like a runaway cultural typology, in the shifting blades of grass moving between grant applications, meeting sessions, constant pruning and refurbishing of its idea and physical grounds. The idea of “instant” both mocks and celebrates the same marketable speech that brought you products like Tang, Nescafé, and other forms of commercial convenience. But if you dig deeper, you touch on the poetry of art making itself, which is the practice and realization of the output given in temporary aesthetic experiments. While Franke provides the stage, her decision to launch her own artist-run space from her home in 2004 coordinated with a global moment where various art communities led by individuals – having access to private property – began to blend their creativity with their domestic or dwelling situations. Not that such approaches to artistic creation have not been available before in art history (however, strangely, one does not imagine Donald Judd’s Marfa as a posthumous artist-run space), but the power orientation is different; here the artists is, well, running things (unlike the art collector, curator, or aficionado in previous iterations of the art institution).

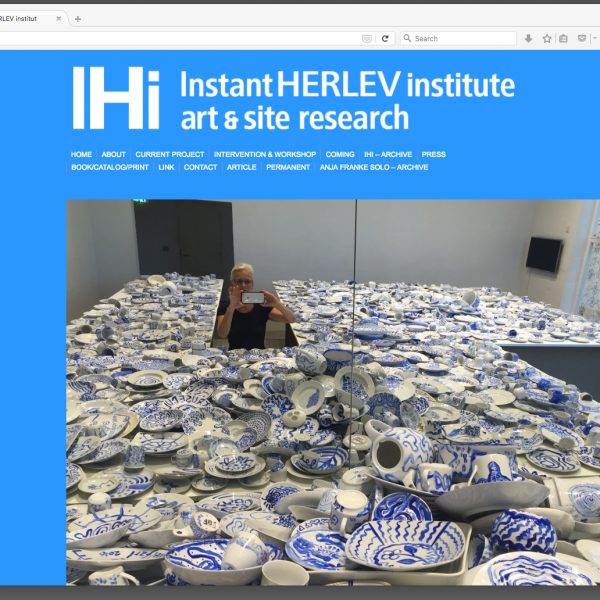

InstantHERLEV institute, 2014. Image by Anja Franke.

By opening their properties to new forms of cultural organization and changing the order of previously expressed ideas about how contemporary art is organized for the public [i.e., through the gaze and outcomes of art’s ruling institutions], the artist connects with her true totemic variable – aesthetic life. Where the cultural designs of these self-organized artist-run spaces present us with a counter-logic to the order and regime of contemporary art’s legitimacy and raison d’être, and in doing so, heighten the evidence that art is not a belief system nor a hobby of a particular partisan politic. Instead, such pure acts of intention are as close as we can get in form and content to public displays of knowledge. Of these, you can mention a whole list of people, too long to mark here. But in a real sense, this points to the fact that while a self-organized theory of relational activity driven by artistic interventions is occurring in practice – the various publics meeting upon these productions are the idea and motivation behind transforming unsuspecting spaces in suburbia into cultural centers.

The artist is perhaps the last and first profession that both gentrifies and de-gentrifies geographies. For this reason, the artists running these are diversifying the historical value of a region or local setting and, at the same time, building – in better cases – the area’s cultural heritage and its inalienability. But as well, something else happens in an era governed by the rise of credentialism and “scientific” managers, the articulation and honing of the communities, relations, and conditions for which artist-run spaces make their productions available results in forming highly sophisticated cultural managers – making people in the process, who are well aware of the tentative ebbs and flows of changing conditions for the role of culture in their neighborhoods and cities. In many ways, it is a strange occurrence that with the large deskilling of artistic labor from the late 70s to today; artists managing their own cultural spaces are situating and manufacturing the future of labor; primarily through new forms of engagement and recognition that connect with the various subtleties of networks, relevance, establishment, and communication.

To some extent, we have to agree on where we stand today vis-à-vis contemporary art and the independent productions outside of its heterogenous, established institutions. Rather than saying it is broken (as I am sure some would gladly jump to that conclusion), we are enjoying a post-contemporary moment, where artist-run institutions are blossoming as parallel alternatives to cultural experience, especially concerning the cultural regimes that historically have enjoyed the comfortable position of moderating and distributing contemporary art’s categories for audiences. In this new sense, who gets to create what is contemporary? And if it occurs at a very localized level, how does it work, interrogate, or rethink art historical canons? More accurately, how are these registered in a progressive understanding of history and culture? These questions emerge because the microcosms of community life, their challenges, crises, and the aesthetics that make them flourish are discarding and redefining master narratives. Practices like Anja Franke’s are first to integrate with this community life and, through a wide variety of organic, historical, social, and technical subjectivities, produce new and alternative directions from the non-linear objectives of post-contemporary art.